What the F16 decision tells us about US support to Ukraine

The coming election season in America means there are already starting to be limits placed on its support to Ukraine.

At the end of last week, President Biden agreed to let European countries send their mothballed F-16 fighter jets to Ukraine. This is a major success for Ukraine which has hitherto had to rely on outdated Soviet-era planes. For the first time Ukraine will have a fighter jet with a performance that is equal to, or better than that of their Russian opponents’ Su-34. Whilst America is not expected to provide any jets itself, its permission to others to provide theirs is a significant development.

American reluctance

It is particularly significant because this was resisted for so long by America. Whilst President Biden has undoubtedly led the way in providing support to Ukraine, there have been clear limits on what America, or at least the White House, is willing to offer. One of these has been F-16s. The Biden administration had stated that it would not let Ukraine have these fighters, repeatedly and clearly, as recently as late January this year. Concerns over Ukraine’s ability to operate and maintain these fairly complex aircraft, as well as concerns of escalation that they might be used to strike targets inside Russia, appeared to be holding back the normally bullish Americans.

In response to this seemingly firm line from the White House, European countries began a concerted campaign to soften up America ahead of the G7 summit. The Netherlands repeatedly announced it was starting a dialogue with Ukraine on sending its unused F-16s. The Netherlands and UK Prime Ministers Rishi Sunk and Mark Rutte announced they would be training Ukrainian pilots, which was then echoed by France. With a sense of gathering momentum, Denmark and Belgium joined the Netherlands in offering unused aircraft. Whether this was a co-ordinated European campaign to shift America, or a happy coincidence of activities can be debated. But the outcome was clear - America caved in at the G7.

The phenomenon of European countries getting ahead of American in support for Ukraine, rather than needing to be nudged along by the Americans, feels new. And it tells us something about the political climate Biden faces at home. He seems likely to be facing Donald Trump in the next presidential election. Trump has made his opposition to supporting Ukraine abundantly clear. This is perhaps unsurprising, as in Trump’s warped worldview, the Ukrainians are at fault for his first impeachment. What has been more surprising is the spectre of Ron DeSantis and other supposedly mainstream republicans adopting a similar position. With this public support in the US brittle on Ukraine, the risk of escalation, perhaps with a major Ukrainian airstrike on a Russian city, for example, is a nightmare scenario for Biden which could easily be weaponised by his opponents.

For similar reasons, Biden’s White House is also resisting a roadmap for Ukraine to join NATO, something I wrote about in The New European. This is not to say that America is opposed to Ukraine’s membership: on the contrary it has championed it over decades. But it is opposed to there being a clear pathway currently to Ukraine actually joining. The worst-case scenario of a divided US finding itself in direct conflict with Russia in an election year is not something that Biden wants to entertain.

Reluctance, but still essential

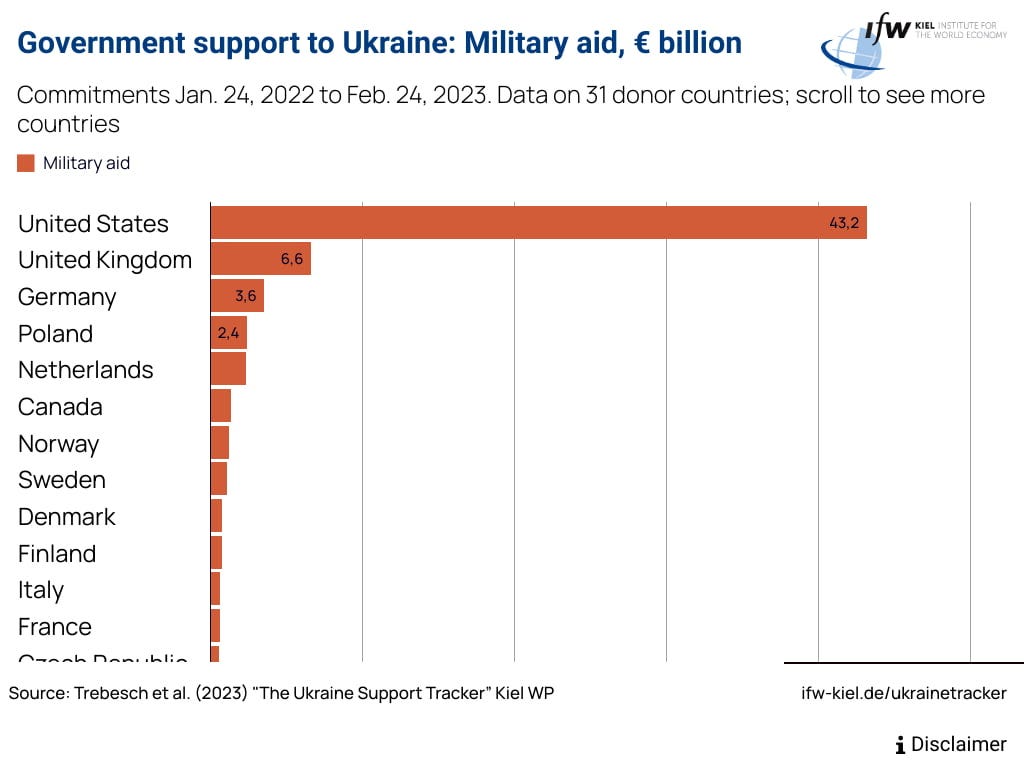

This account of American reluctance over aspects of its support to Ukraine should not be mistaken for overall backsliding by America, which is still by far the biggest military and civilian donor. But the complexities of America’s broken domestic politics do mean that this current support might have to be time limited, or at least heavily circumscribed by the time we get into 2024. And it also shows us how far Europe has come. In the space of 18 months it has gone from (in some cases) outright opposition to arming Ukraine to being the ones dragging along a reluctant America. Is it too much to hope that Europe might step up further, to reduce America’s burden?